An Old College Sports Film for Our Time

Plus: Revelations from Mizzou, Cal athlete exit interviews and Jon Rothstein's texts are even worse than his tweets.

This is Newsletter of Intent, a free weekly emailed dispatch from The Intercollegiate. To learn more about us visit www.theintercollegiate.com.

Subscribe to the weekly Intercollegiate Podcast.

Scroll to the end to learn about our creative partner, the College Sport Research Institute.

Ready to commit to your college sports education?

By Luke Cyphers and Daniel Libit

Movies tackling the unsavory side of college sports — from “Blue Chips” to “The Program” to “He Got Game” — are nothing new, and have often been lauded for exposing the dire costs and hypocrisy inherent in what the NCAA likes to call “the collegiate model.”

But a nearly forgotten 1933 film from the legendary Hollywood director William A. Wellman may be the most unflinching, sociopathic look at intercollegiate athletics ever produced—and the most instructive for would-be college sports reformers.

It’s called “College Coach,” and this raggedly executed examination of the dark, absurd heart of college football stands out because it could easily be remade today — by the Coen Brothers, Quentin Tarantino or Ryan Coogler.

Though the picture is dated, when it comes to the game itself, there’s nothing in the 86-year-old film that feels anachronistic in 2019: academic fraud, on-field brutality, and supposedly august institutions captured by, and complicit in, abject hucksterism.

What is different? The film decides, in the end, there’s absolutely nothing to be done about it.

Nearly nine decades after it was made, “College Coach” still gets to the nub of why modern college football is so resistant to a revolution: Soul-destroying, bandit-capitalist nihilism sparks joy.

Though the film still appears occasionally on Turner Classic Movies, if it’s thought of at all these days, it’s little more than trivia fodder.

A young John Wayne, himself a former football player at USC, has an uncredited cameo.

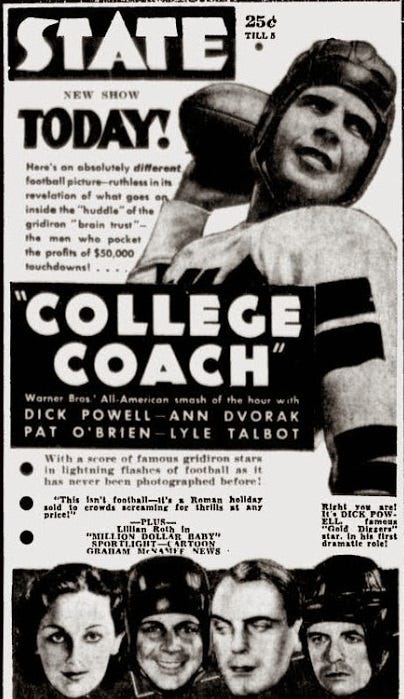

Pat O’Brien inhabiting the title role is fascinating, given his professional arc. Just seven years after he played the shameless antihero in “College Coach,” O’Brien cemented the myth of big-time coaches as iconic molders of men in “Knute Rockne, All-American.”

Then there’s, of course, Wellman, a brawling, pioneering maverick who directed the first Oscar-winning Best Picture, “Wings,” and several other influential twentieth-century films, including “The Public Enemy,” “The Call of the Wild,” “Beau Geste” and the original version of “A Star Is Born.”

“College Coach” is worth a reconsideration now because, unlike its genre successors, it suffered no illusions about football, higher education or the coaching profession. “Right now, I’m the best football coach in the world,” says O’Brien, as Coach Gore, early in the film. “But it’s a racket. A racket where they catch up to ya awful quick. Let’s cash in on it while we can.”

Gore enriches himself with big-money merchandising agreements and media contracts, including a shoe deal, a radio show, and an autobiography, “My Life in Amateur Football.”

The coach isn’t the only one on the take. Academic institutions are willing to sell out any and all principles for the promise of gridiron glory and the dollars it brings. “Our big mistake was financing the new science lab,” says an administrator.

The players get paid under the table and don’t bother to pretend otherwise, though they do pretend to go to rigged classes. Even the dimwits, which is most of them. “Now there’s nothing in these courses that’s likely to keep them up nights, is there, professor?” Gore asks the team’s academic adviser.

The adviser assures him that’s not a problem, and tells the coach that Matthews, a backfield ace, will major in Aesthetics. To which Matthews replies, “OK, except I can’t spell what I’m majorin’ in.”

A bumbling lineman threatens to transfer: “Me goin’ Atlantic Eastern College. They make me fine big offer. Every week check I get 50 bucks. With besides automobile drive myself. Anyplace I want go … She got six cylinders.”

The canny Coach Gore makes a deal to keep the player on the roster: “I’ll get you one with seven cylinders.”

There are locker-room fistfights (encouraged by the coach), a star player who tries to sleep with the coach’s wife (not encouraged by the coach), and a scandalous insider real-estate deal centering on construction of a new stadium (instigated by the coach).

Does any of this seem familiar?

Nobody saw “College Coach” as among Wellman’s best work, certainly not the man himself. “It was not a film my father appreciated,” the director’s son, William Wellman Jr., tells NOI.

Wellman Jr. grew up among Hollywood royalty, and he went on to his own career as an actor, director and writer. He penned an entertaining biography of his father, and today, in his 80s, still gives lectures on Hollywood history.

The younger Wellman says his old man would have no problem with somebody remaking “College Coach,” or any of his movies. His dad once told him, “Bill, if it was good once, it can be good again.”

The success of all three reboots of “A Star is Born” is proof.

But at the time, few thought “College Coach” was good. The biggest issue was its casting, with Dick Powell in the role of Phil Sargent, the team’s conscientious star quarterback.

Powell was a heartthrob in early musicals, known for sappy ballads. “This was his first so-called dramatic role,” Wellman Jr. says, “and I thought it was ridiculous for him to be cast as a football player. There’s even a scene where he’s singing and tinkling the ivories.”

Almost any of the contract players for Warner Bros. would have worked better. Just two years earlier, Wellman directed James Cagney’s electrifying performance in “The Public Enemy,” and the director and actor were good friends. “Cagney could have played that role,” Wellman Jr. says. “You’d have bought it.”

But Wellman was stuck with Powell, and “College Coach” never became more than a puzzling product of its genre. And yes, college football films were a genre in the 1930s, a way to wring money from the sport’s rapidly growing fan base.

Many of these movies were credulous tales inspired by Grantland Rice and the other the sycophantic, “Gee Whiz” sports writers of the day.

As the invaluable sports historian Murry Sperber pointed out in his 1998 book, “Onward to Victory: The Crises that Shaped College Sports”:

‘Gee Whiz’ sports journalism connected directly to athlete-hero juvenile fiction—some writers worked in both fields—and its product, in its simplest form, was the journalistic equivalent of Hollywood’s primitive college football films.

For a while, there was a counter-narrative, the “Aw Nuts” school of sports writing. A 1929 Carnegie Foundation report on corruption in college athletics proved a boon to the “Aw Nuts” view, as Sperber writes:

The report confirmed with hundreds of pages of data what the “Aw-Nuts” skeptics had long argued: College football was a huge commercial enterprise and its famous coaches, including Knute Rockne, were among the greatest self-promoters and buccaneers of the 1920s. The Aw-Nuts writers kept the issue of commercialism and corruption in intercollegiate athletics alive during the 1930s, preparing the public for further Carnegie “Bulletins” as well as Hollywood depictions of their criticisms of college sports.

While gee-whizzing flicks like “The Spirit of Notre Dame” and “Navy Blue and Gold” pumped out propaganda, Sperber points out that “Aw-Nuts” football stories also made it to the big screen. “Touchdown” in 1931 features a vile coach who lures players to campus with big payments and forces them to play injured, endangering their careers and lives.

Then there was the brutal satire of the Marx Brothers’ 1932 “Horse Feathers,” in which university leaders decide to tear down the college, including the dorms, to pay for a football stadium. When the faculty asks where the students will sleep, the college president played by Groucho Marx responds: “Where they always sleep. In the classroom.”

“College Coach” couldn’t seem to figure out where it was on the Whiz/Nuts spectrum, and with a final act that can only be described as bonkers, the movie winds up falling into an utterly cynical gray area, one today’s kids might call “Deze Nuts.”

Which is why it’s so relevant now.

Just like the fedora-topped reporters in “College Coach,” who normalize or ignore the systematic corruption of higher education because a winning team is “good copy,” the modern media band plays on, accompanied by a chorus of victory-hungry fans.

Wellman plays some of this corruption for laughs, and effectively, with a spicy Pre-Code Hollywood script.

“How’d ya like to sick a finger in her coffee?” says a lascivious player.

“They’re making me an honorary Woodpecker,” a booster tells Coach Gore at a speaking engagement for a Boy Scouts-like organization, and then points to his friend. “He’s a ‘pecker, too.”

But throughout much of its uneven 75 minutes, the film shakes its head and frowns on scandal, setting itself up as a formulaic Aw Nuts morality play about sportsmen gone bad.

The coach wins the conference championship and fills the stands thanks to his rampant cheating, but the coaching racket catches up to him awful quick. In his second season, with his roster depleted by his prior bad acts, Gore’s team struggles. The season finale becomes a true must-win game; a loss would blow up the financing of the coach’s stadium scheme and send him to “the poor house.”

Gore seems headed for a deserved comeuppance. Except that’s not what happens.

At the film’s climax, Phil Sargent, Powell’s miscast quarterback, who had quit the team because football was getting in the way of his chemistry classes, is coaxed into rejoining the squad for the dying moments of the final game. So too is the character who’d been expelled for trying to shag the coach’s wife. Thanks to the prodigal players, the team comes from behind for the victory, and …

The team erupts in celebration. So does the coach. So does his long-suffering wife. So does a chemistry professor who had previously been disgusted with the university swapping its integrity for football.

It’s an ending rendered even happier when Coach and Mrs. Gore, who’d vowed to slow down and work on their troubled marriage, abruptly decide to leave for a better-paying job at a bigger school.

In the 1993 James Caan film, “The Program,” victory in the climactic big game is a temporary triumph for the beleaguered players and coaches over a crushing system. In contrast, “College Coach” glories in the victory of the corrupt system itself: a cleat stamping on a human face—forever.

Intentionally or not, Wellman throws down a gauntlet for anybody who believes the games we watch can uphold quaint notions like sportsmanship and fairness, or that they can be reformed in any meaningful way.

In his final pre-game speech, Gore extols the most salient value in this world, then and still. “There's a crazy, daffy crowd out there screaming for a hundred thousand dollars worth a ball game,” he says. “Now go on out and deliver.”

Flawed and dated though it is, this little relic of a movie casts light on why today’s NCAA reformers have such a Sisyphean task. For more than a century, there’s been a rabid audience for the spectacle of college football, a crazy, daffy crowd that doesn’t care about hypocrisy, overlooks scandal, ignores player safety, and worships flimflam men posing as coaches—so long as they put people on the field who go out and deliver.

MORE EXIT INTERVIEWS: MIZZOU & CAL

This newsletter started with our publishing of thousands of pages of materials from Division I athlete exit and end-of-season interviews, which we obtained through public records requests. We’ve now updated our online library with documents from two more schools, Missouri and UC Berkeley.

Unsafe medical and training practices have been a regular and disquieting feature of college sports programs over the past decade. So, it came as no surprise when we saw the issue pop up at Mizzou.

But the language in an internal school memo, summarizing last year’s exit interviews with 19 football players, is still still eye-opening:

Several football student-athletes expressed serious concerns regarding the Sports Medicine program and the culture of the training room. One student-athlete described his experience as “being failed by the training staff.” All student-athletes who voiced concerns about the medical treatment they received stated they were doing so to prevent other student-athletes from having to go through what they experienced…”

The document goes on to cite athletes reporting delays in receiving “appropriate treatment” that led to “prolonged recovery.” Players worried the delays would affect “their ability to be ready for the NFL draft, limiting their opportunities to play professionally.”

The summary also states:

Student-athletes were made to feel that they were “the problem,” ie, responsible for their injury and prolonged recovery. Some student-athletes also reported that the training room is not welcoming and that some athletic trainers appear reluctant to do their job; in particular, student-athletes with chronic injuries or who do not play are begrudgingly treated.

The documents are heavily redacted, as this screenshot from one of the interviews illustrates:

NOI contacted Missouri to ask what, if anything, the university did to address the athletes’ concerns. Nick Joos, a Mizzou spokesman, responded in an email:

In the past year as the new South End Zone Facility was opened, which features an extensive athletic training area, some structural changes were made with staff responsibilities to help ensure appropriate oversight and resources were being dedicated to all of our sport programs.

Last summer, Associate AD/Medicine Rex Sharp, who had been the Tigers’ head trainer since 1996, was reportedly replaced as the football team’s primary trainer, although he still oversees the university’s sports medicine center and supervises the entire athletics training staff.

A gendered fault line showed up in the sport of track and field, where male athletes believed they were getting short shrift—complaints summarized in Missouri’s Spring 2019 report under Areas of Concern:

The distance track and field student-athletes expressed concerns with the current state and future of the men’s distance program. They felt that the large women’s roster (~35 student-athletes) and diminishing men’s roster (~15) is negatively impacting the men’s program. From the student-athletes’ perspective a significant portion of the women’s team is not committed to athletic success and, as a result, they make choices that are detrimental to performance (e.g., alcohol consumption, lack of effort at workouts).

They also believed they knew the culprit:

Because of Title IX, the coaches cannot cut student athletes who are not committed to the program. Permitting these student-athletes to remain part of the team has a negative impact on team culture, devalues the meaning of wearing “Mizzou” on the jersey and is detrimental to the men’s program. The size of the men’s team is restricted and Missouri talent is not going to Mizzou.

And they offered solutions:

They suggested having “A” and “B” teams who would practice at different times and receive different level (sic) of equipment support. The other suggestion was to hire a “hands-on” assistant coach as part of the problem is that Coach Burns cannot give enough individual attention with such a big roster.

The Title IX complaints came exclusively from male athletes, though one woman runner noted “a lack of collective commitment to winning,” stating that team rules were “not enforced,” which sent “mixed messages about expectations.”

Some university athletics programs have been accused of circumventing Title IX equal opportunity requirements by creating “Potemkin” teams of non-competitive athletes to build up female athlete numbers, as this 2011 New York Times story revealed.

It’s also true that non-revenue sports for both genders often lose out to titanic football programs in intra-departmental battles for resources, which the interviews with Mizzou athletes in the throwing events highlighted:

...they noted disparity among sports in access to the weight room. They also noted that they cannot use their indoor facility at the Hearnes Center until after November because of football.

Joos responded to follow-up questions about the track interviews without really addressing them. “We consider student-athlete feedback as well as a myriad of other information we gather during the course of the year in order to provide a supportive environment for our student-athletes to excel in academically and athletically,” he wrote.

Finally, Missouri’s 2015 anti-racism protests also figure in last year’s exit interviews. The student movement four years ago threw a spotlight on racist incidents and a broader atmosphere of intolerance on the university’s campus. Shortly after Mizzou football players joined the protests and vowed not to take the field in an upcoming game unless student demands were met, the university president resigned.

Sprinkled throughout the Fall 2018 exit interviews were comments from athletes, most of whom were freshmen at the time of the protests, who said the events had a profound effect on them—and their school.

One player, for example, said the culture of the team was in “much better shape,” and that the “campus has been more responsible because nobody wants to go back to … 2015.”

Another player noticed “much more integration across racial/ethnic groups across campus” and cited as an example “3 or 4 white guys pledging historically black fraternities.”

The protests drew heavy criticism in some quarters, and were blamed for steep drops in freshman enrollment on the Columbia campus over the next two years.

That decline has reversed recently, and Missouri is now bucking national enrollment trends.

Meanwhile, Cal provided us heavily-redacted summaries of end-of-season interviews for each team sport, besides than men’s basketball and football. According to athletic department spokesman Herb Benenson, the school didn’t interview basketball players at the end of last season because there was a coaching change; the football survey documents are apparently still forthcoming.

Despite the latticework of black redaction bars, one Cal team’s problems really stood out: of the 14 Cal softball players who were interviewed, none responded as having an above-average experience.

That might be surprising to an outsider, given the program is helmed by the storied Diane Ninemire, now in her 33rd year coaching the Golden Bears. There appears to be lots and lots of athlete feedback in the documents, but scarcely any that the school would allow us to see.

When we inquired about the negativity surrounding last year’s softball team, Benenson suggested that the players’ problems largely related to facilities:

[W]e are presently investing more into the program, including in recruiting and in a new facility. Once completed, the softball stadium will include locker rooms, fixed seating for 1,500 fans, enclosed batting catches, a video board, field lighting and a press box that will enable the team to host NCAA Tournament games – all elements that the program does not currently enjoy and are important features based on feedback from student-athletes and the softball community.

Was this really the extent of the complaints? Perhaps some enterprising reporter at The Daily Californian will dig further.

HOW TO TEXT LIKE A CBB “INSIDER”

As a new college sports publication, we’re always interested in learning the ropes from those in the know. How do you build an audience? How do you make yourself relevant? How do you develop key sources? We have some intuitions, but we’re always game to pick up new tactics from the true masters of the beat.

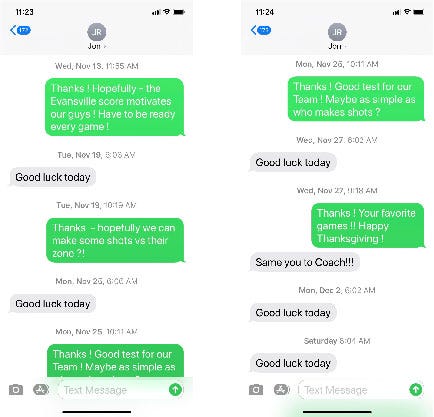

Like Jon Rothstein, CBS Sports’s “College Basketball Insider”, who has marked off an indelible niche through sheer — how should we put this? — indefatigability. For one thing, there doesn’t seem to be a nugget of college basketball news too trivial, from a team too forgettable, which Rothstein won’t glowingly hype on Twitter. His singular brand of — what might we call it? — reporting has won him some 190,000 Twitter followers, a regular New York Times (!!!) column, and the bemused attention of his media brethren.

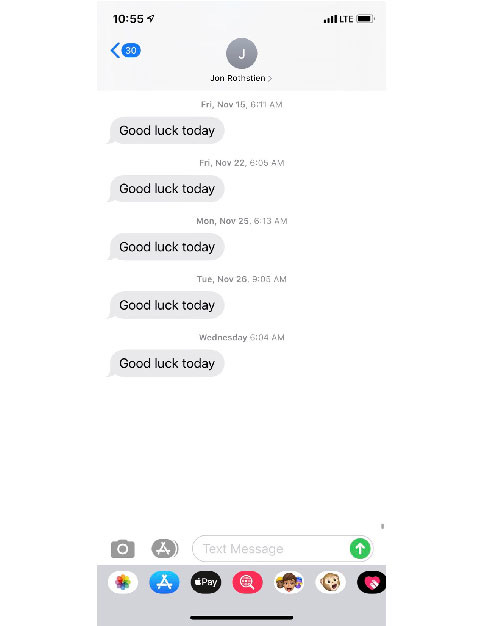

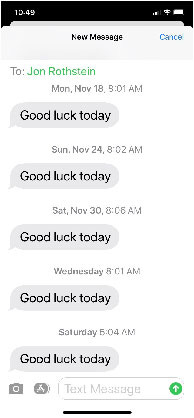

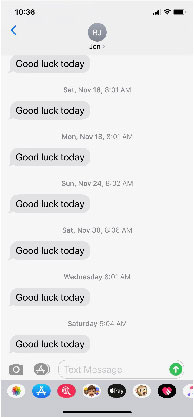

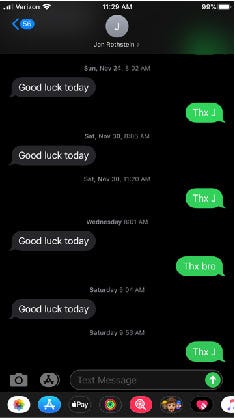

As part of all this, Rothstein has also become, as successful people often are, the subject of some rather scurrilous rumors and innuendo: e.g., that he might not be sentient. So, we were a more than a little skeptical when we heard, some time back, that Rothstein, throughout the college basketball season, sends a “good luck” text message to every Division I coach before each game. Stadium’s “Basketball Insider” Jeff Goodman has also, in recent years, tweeted several snarky references to his competitor’s alleged texting regimen.

But come on: who would have the time to text every coach before every game? And even if this project could somehow be sufficiently streamlined — mass-texting, SMS bots, Keebler elves — who would be that obsequious?

Anyway, last week, we started making some public records requests of some Division I schools, seeking text message communications between Rothstein and their basketball coaches over the last few weeks. You know, just to put this to rest.

Well, we can already now confirm that Jon Rothstein does not send “good luck” text messages to every DI college basketball coach, before each game. For example, he appears not to have given his blessing to the Idaho Vandals coaches, who surely could’ve used it. Ditto for the coaches at Eastern Washington, who, according to the school’s public records custodian, “do not know who Mr. Rothstein is.” But these might be the outliers, because, according to our records requests…

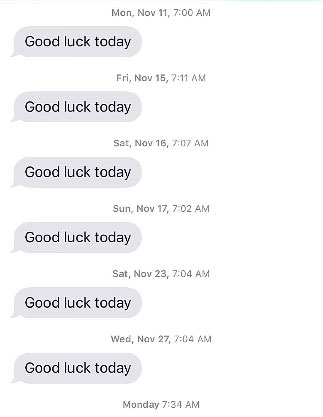

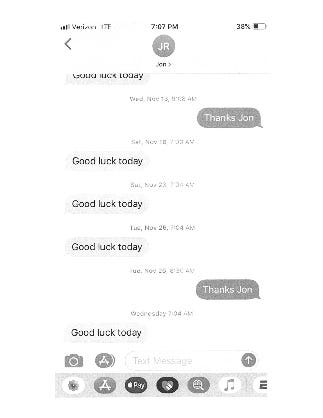

Rothstein did send multiple “good luck” texts to Kansas State head coach Bruce Weber:

And Florida Gulf Coast’s Michael Fly:

And Nebraska’s Fred Hoiberg, who never replied:

And Colorado head coach Tad Boyle, who never replied:

And Colorado assistant Bill Grier, who never replied:

And Colorado’s other assistant, Anthony Coleman, who apparently handles the Rothstein duties for the Buffs:

And Stony Brook associate head coach Bryan Weber:

And the New Jersey Institute of Technology head coach Jeff Rafferty, who needs to charge his phone:

And…OK! Stop! Uncle! This is getting way too weird. For one thing, we rarely get public records requests returned within a few weeks, let alone a few days. (It’s nice to see college athletic departments can really hop to it when they want to.) Secondly — and seriously — what kind of journalist does this?

And yes, Rothstein does publicly self-identify as a journalist. (And yes, we reiterate, he is a New York Times contributor.)

Rothstein did not respond to an email seeking comment about his “good luck” text messages, which, regrettably, we continue to receive in droves.

But here’s some declarative wisdom that likely won’t materialize into one of his daily aphorism tweets: Real journalists FOIA, not fawn.

Now, that’s a t-shirt we’d wear.

Daniel Libit and Luke Cyphers, coeditors of The Intercollegiate, write Newsletter of Intent each week. You can reach them with questions, comments, tips and “good luck” messages at dlibit@theintercollegiate.com and lcyphers@theintercollegiate.com. NOI will be taking a holiday break next week, returning to your inbox on Dec. 31.

Featured photo from Annyas.com / Movie Title Stills Collection

The Intercollegiate is proud to partner with the College Sport Research Institute, an academic center housed within the Department of Sport and Entertainment Management at the University of South Carolina. CSRI’s mission is to encourage and support interdisciplinary and inter-university collaborative college-sport research, serve as a research consortium for college-sport researchers from across the United States, and disseminate college-sport research results to academics, college-sport practitioners and the general public. You can learn more by visiting CSRI’s website.