The Case for an Athlete Coogan Law

Plus: Ted Agu's accountability guardian digs for one more doc and Jon Krakauer tries to scale Mt. FERPA

This is Newsletter of Intent, a free weekly emailed dispatch from The Intercollegiate. To learn more about us visit www.theintercollegiate.com.

Subscribe to the weekly Intercollegiate Podcast.

Scroll to the end to learn about our creative partner, the College Sport Research Institute.

Ready to commit to your college sports education?

By Luke Cyphers and Daniel Libit

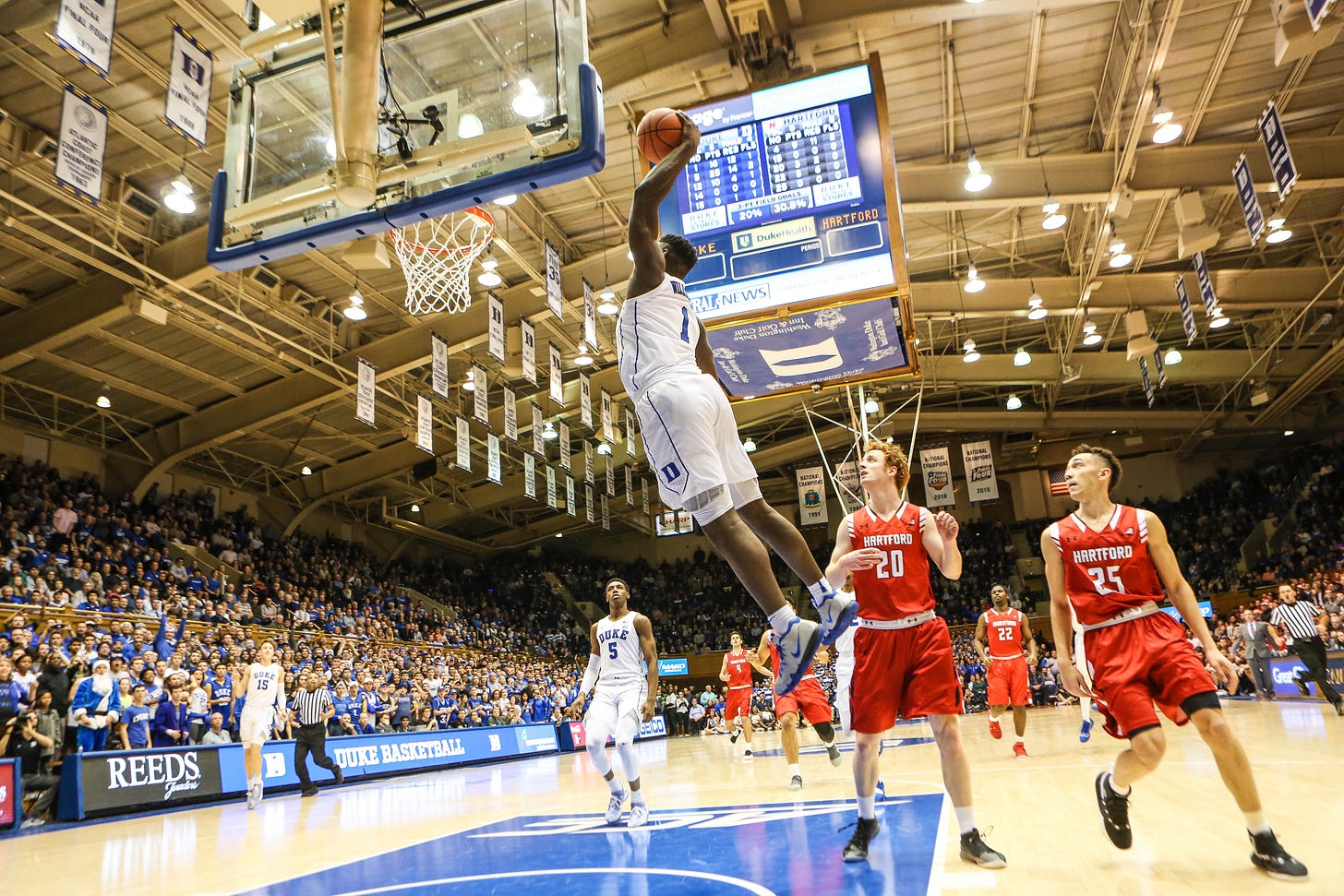

Zion Williamson bears little physical resemblance to Uncle Fester.

But the chiseled NBA rookie and the lumpy actor cast in the original “Addams Family” series, Jackie Coogan, have more in common than electrifying talents.

Both were child stars. Both became iconic in movements aimed at changing power structures in the entertainment business. And both of their situations point to a blind spot in the roiling debates over how to reform the NCAA’s archaic amateurism rules.

Namely, at what point are elite young athletes entitled to their full economic rights—including a share of the income they produce?

The career experiences of both Williamson, the No. 1 draft pick of the New Orleans Pelicans, and Coogan, whose name is on a canonical California law protecting the earnings of child entertainers, show that the current wave of amateurism reforms need to address athletes long before they step on campus.

Let’s take Williamson first. When the Duke forward’s shoe burst open and his knee sprained in a nationally televised game against North Carolina last February, it targeted a laser pointer on everything that’s wrong with college sports’ economic structure. A young, charismatic, ethereally talented African American performer drew an audience of millions, creating abundant wealth for his school, his coach, his school, a sneaker company and more than one TV network, all while risking his health and his considerable future earnings—which looked to be in jeopardy when he limped off the court against UNC.

Yet by NCAA decree, Williamson couldn’t earn a dime from it.

The hypocrisy was too blatant to ignore, and the exploding Nike was a shot heard round the world, providing justification for state legislative efforts giving college athletes the legal right to profit off their names, images or likenesses. California passed the first such NIL law, which goes into effect in 2023, but several other states are right behind, and some, such as Florida, could have their laws operational as soon as next year.

But truth be told, the NCAA had been shorting Williamson long before that February game against Carolina. His athleticism and mastery of the slam dunk made him a brand name years before he matriculated at Duke. Williamson's Ballislife.com senior year mixtape

had already logged millions of views on YouTube, as had a highlight package of Williamson’s 2017 AAU clash against LaMelo Ball. Williamson had more than 1 million Instagram followers, exceeding most NBA players, by the start of his senior high-school season.

And yet, according to the NCAA, Williamson couldn’t earn a dime from that, either, without sacrificing his college eligibility.

That’s where Coogan comes in. Or at least should come in.

Jackie Coogan was discovered by Charlie Chaplin in 1919, co-starred with the Hollywood legend in the smash hit, “The Kid,” and was one of the most marketable stars of the silent movie era, making an estimated $2 million to $4 million as a child. But when he tried to claim his money after turning 21, he discovered his parents and his manager had spent almost all of it. Under huge public pressure, the state passed The California Child Actor’s Bill, popularly known as the Coogan Act, in 1939, mandating trust funds to protect a percentage of minors’ earnings. Other states with significant entertainment industries, most notably New York, have versions of the law, and California has updated it several times, formally including young athletes under the statute in 2000.

And this is where the new California NIL law for collegians gets interesting.

Richard Hunter, a legal studies professor at Seton Hall University, and his colleague John H. Shannon, have written extensively on sports law issues, including this 2015 Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review article that recommends expanding more Coogan-style protections to athletes who are minors.

The world has changed in the four years since that article, and is much more open to the idea of college athletes earning money, at least from endorsements.

“First of all, the courts decided in O’Bannon and other cases that clearly the athletes were entitled to compensation if their name, likeness and image were used,” Hunter tells Newsletter of Intent. “Everyone agrees on that. It’s out of the barn whether the athlete is going to receive remuneration, on fairness grounds and other grounds. No. 2, though, is how much are they entitled to? And No. 3 is, at what point do they get it?”

For instance, a decent number of high-profile athletes enter college before their 18th birthday and would be considered minors.

“When athletes have the right to be paid in a place like California that has a mandatory Coogan requirement, in those situations where the athlete is not yet of legal age, the question is, does the Coogan Law apply?” says Larry Elkin, president of Palisades Hudson Financial Group, which represents underage clients in the music and movie industry. “I think it probably does. I would insist, as the [film] studios do now, that there be a Coogan account in which they can deposit money.”

Another issue is that while the California NIL law protects the scholarship and eligibility of athletes who, say, make money off autographs, or endorsements, or self-produced YouTube videos, it doesn’t address pre-college athletes. As this article from the National Federation of State High School Association’s website points out:

“The bill does not apply to high school student-athletes and does not empower them to earn NIL profits in violation of California Interscholastic Federation amateurism rules.”

So the next Zion Williamson could sign a sneaker endorsement deal at 14 without jeopardizing NCAA eligibility in California, but he couldn’t play for his local scholastic team.

For the top basketball players, though, that may not be much of an issue. As Luke has documented, the last decade has seen an explosion of hoops-centric prep schools, some of them shady to the point of criminality, which play national schedules and don’t bother joining state activities associations or following their rules.

It’s not hard to imagine these bootleg preps welcoming teens with endorsement deals—and finagling ways to separate those teens from their money.

That’s why amateurism reforms must go beyond the NCAA and deal with the entire elite youth sports system, which — from parental misdeeds to coaching abuses to concussion treatment to sexual assaults — seems to be in a perpetual state of crisis. It’s not just the NCAA that’s a problem; it’s the entire professional sports feeder system.

A 2015 Marquette Sports Law Review article by former college athlete Kristin Hoffman makes the point that elite youth sports training frequently resembles abusive child labor. She used figure skating and gymnastics as examples—and this was before the Larry Nassar atrocities became public. Hoffman advocates for more systematic legal protections for skaters and gymnasts, modeling potential reforms on the Fair Labor Standards Act and on Coogan laws.

It’s an idea that can be applied to football and basketball players, too.

Hunter believes the financial issues coming to the fore with NIL create an opportunity across sports, one that can be addressed by mandating that minor athletes who receive any remuneration could not receive that money without having a certified financial adviser. “Make sure that adviser is qualified and registered with the state,” Hunter says. “That would go along with the Coogan idea, that you’re not going to have a Joe Shlabotnik off the street who’s going to steal your money. Because that’s what’s going to happen to some of these athletes. All their money’s going to be stolen.”

He adds: “You know who usually steals their money? Their parents. So I think you have to take into account that the parent has to be involved, so you could mandate that the parent has to get the assistance of a financial person.”

Elkin likewise sees potential for real reforms, partly because NIL is so easy for the public to understand. “We are all born with our own image and likeness,” he says. “And our parents give us our name. When we leave the hospital, we’re equipped with all of those things. And it’s only when we arrive in college that the NCAA informs some of us that it now controls the rights to those assets, and maybe it will or maybe it won’t permit us to exploit that which was ours. It’s fundamentally wrong. And people are recognizing that.”

Beyond that, Elkin says, “There’s an increasingly broad recognition that there’s really no difference between entertainment and sports. Everybody knows and understands and expects that a child who appears in a film or a TV show or a commercial should expect to get paid if it’s a commercial venture. And I think a large section of the public now sees athletes as no different.”

Though the NCAA may not yet realize it, the reformers have probably already won the culture war over payments to elite young athletes. The tricky thing now will be negotiating the terms of the peace, and ensuring that future athletes weren’t saved from one exploitative system only to be devoured by another.

TED AGU’S ACCOUNTABILITY GUARDIAN

On Thursday, a hearing is scheduled in Alameda County Superior Court as part of journalist Irvin Muchnick’s ongoing public records lawsuit against the University of California, Berkeley.

In one sense, the matter at hand is relatively minor: a fight over the un-redacted release of a single email, sent by a Cal athletic official five years ago, in the immediate aftermath of football player Ted Agu’s death.

And yet, the motion before Judge Jeffrey Brand offers perhaps one last chance for public accountability to log a definitive victory in a tragic story succeeded by years of deception and stonewalling.

In two previous rounds before this court, Muchnick has come up empty — even though, through sheer persistence, he has found other avenues to revealing documents, including a 141-page binder of police investigation records, leaked by a campus source, which university officials had tried to keep under wraps.

Muchnick is no stranger to sports reporting rabbit holes and lone-wolf undertakings, having spent nearly 30 years beating the bushes over the unsolved homicide of former wrestling star Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s girlfriend. He has spent the last two decades fixated on the sporting scourges of sexual abuse and head trauma, and has become particularly interested in the underreported ravages of the American football industrial complex.

“People need to understand they don’t just happen at Penn State and Baylor, they happen at the world’s leading public institution of higher learning,” Muchnick tells NOI. “If you are in the football business, you are going to be dirty, no matter how pristine your institution is in other areas.”

That, he says, is why accountability is so important in the case of Ted Agu’s death.

Muchnick’s first post on Concussion Inc., in November 2013, was about a head injury sustained by another Cal football player, Fabiano Hale, at the fisticuffing hands of an incensed teammate. As Muchnick’s reporting helped establish, the attack on Hale may have foreshadowed the death of Agu, who collapsed during a football conditioning drill three months later, in February 2014. Agu was a carrier of the sickle cell trait, which was known to team doctors, and which put Agu at mortal risk during the kind of high-intensity training exercise that ultimately preceded his death.

Since then, Muchnick has carried on as the unpaid accountability guardian, single-handedly trying to hold the line against the natural human impulse and institutional prerogative to just…move…on.

“This is a cover up of a death and I don’t think I should move on from it,” Muchnick says.

At this point, everyone else pretty much has done just that.

In 2016, the university paid Agu’s family $4.75 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit, acknowledging the negligence of its football and strength and conditioning staff in contributing to the player’s death. This admission only came after it was discovered that school officials had willfully withheld essential police and medical information from the Alameda County coroner’s office, including the fact that Agu carried the sickle cell trait, which led the medical examiner to initially and wrongly attribute his cause of death to a form of heart disease.

“In fairness to the University of California, they truly did the right thing,” says Steve Yerrid, a prominent personal injury lawyer who represented Agu’s family.

Yerrid comes from the perspective of having previously represented the family of Ereck Plancher, the former University of Central Florida football player and sickle cell trait carrier, who died during an offseason conditioning drill in 2008. Afterwards, UCF aggressively fought Plancher’s family’s wrongful death claim all the way to the state Supreme Court, which ruled that the school’s damages should be capped at a measly $200,000. (A jury had initially awarded the Planchers $10 million.)

“The University of California, instead of mistreating the parents, paid almost $5 million,” says Yerrid. “That, in and of itself, is a commendable thing.”

As Yerrid points out, the university, as part of its settlement with the Agu family, agreed to initiate a series of reforms to their workout and conditioning protocols and established a permanent physical memorial for the deceased player. Muchnick is much less impressed, noting the recalcitrance with which UC Berkeley conducted two internal reviews, which were mired in conflicts of interest and confirmation bias.

“People have to understand that civil lawsuits that are settled by families that want to move on don’t settle the public interests question about football’s public health deficit in our society,” Muchnick says. “Generally, in my reporting on sports corruption, while I don’t want to blame the victims and I have a lot of sympathy for families … sports parents are not necessarily the ones who have the answers even after they have been wronged. There are larger questions that need to be vetted and discussed.”

In April 2017, Muchnick and his attorney, Roy Gordet, filed suit against UC Berkeley, claiming the school had improperly delayed or denied numerous records requests Muchnick had made relating to Agu’s death. Gordet previously represented Muchnick in a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit they filed against the Department of Homeland Security, seeking immigration records related to an Irish Olympic swimming coach charged with multiple counts of child sexual abuse.

As for his present action against UC Berkeley, after two years of back-and-forth, the case has essentially wound down to a closing determination over whether the university should cough up an April 23, 2014 email, forwarded by Solly Fulp, then Cal’s deputy athletics director, to his father, a retired parks and recreation director in Alaska. Up until now, UC Berkeley has only released a copy of the email thread with everything redacted but the subject heading and recipients.

The subject heading: “Re: Ted Agu - Cause of Death (Statement, Talking Points and Q&A)” — indicated that it might provide some additional insight into how school officials approached the public relations fallout of Agu’s death. UC Berkeley is arguing that because the school’s lawyers were parties to the communication, the materials are privileged. Muchnick contends that this privilege was waived when Fulp forwarded the exchange to someone who was neither a lawyer nor a UC Berkeley employee.

“Our position has nothing to do with the actual contents of the email string in question,” says Dan Mogulof, the school’s assistant vice chancellor. “Our opposition is based on an important matter of principle: defending the inviolable nature of attorney-client privilege.”

Although Fulp, now a Learfield/IMG College executive, is a peripheral figure to the story, most of those in the core cast seem to have made out just fine in the wake of Agu’s death.

Sandy Barbour, then Cal’s athletic director, took the AD job at Penn State (of all places) a few months afterwards. Casey Batten, the Golden Bears team doctor who was accused, in a deposition, of not sharing Agu’s sickle cell history with the county coroner, currently serves as lead primary care physician for the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams. Head football coach Sonny Dykes was fired two seasons later — not because of anything related to player safety, but because the program had suffered consecutive losing seasons and dwindling ticket sales — but was subsequently hired as head coach at SMU, where he remains today.

Most conspicuous, perhaps, is the professional survival of Damon Harrington, the strength and conditioning coach who Cal continued to employ for three more seasons despite a public outcry from the school’s faculty. Harrington, who was at the center of the Agu family’s wrongful death lawsuit, had already been accused of creating an unsafe football workout culture that incited the assault on Fabiano Hale. Nevertheless, only when Dykes was fired for performance reasons in 2017 did the university decline to renew Harrington’s contract. Harrington soon found a landing pad at Grambling, whose head coach, Broderick Fobbs, responded flippantly when pressed by a reporter about his decision to give the star-crossed fitness instructor another shot.

"A second chance is for someone who has done something wrong,” Fobbs pettifogged to the Monroe (La.) News-Star.

(Neither Fobbs, Harrington, nor Grambling AD David Ponton responded to our emails seeking comment.)

And that’s the way the college sports accountability cookie tends to crumble.

Even if Judge Brand rules in Muchnick’s favor, it’s unlikely that anything revealed in that email forward from five years ago will reignite an accountability review at UC Berkeley. Under Dykes’ third-year successor, Justin Wilcox, the Golden Bears are currently 7-5 and destined for a bowl game. Agu’s photo may still hang in the football team’s locker, but everyone’s moved on.

This is how the protected interests of college sports keep the threat of real reform at bay: by slow-walking the full story, such as it is, so that when the totality of the problem finally comes into full view, the only person still staring is a lone, persistent freelance writer with a bug up his ass.

Thank goodness, at least, for him.

JON KRAKAUER TRIES TO SCALE MT. FERPA

Can a well-known writer and a college football hook entice the nation’s highest court to clean up one of our most misconstrued privacy laws?

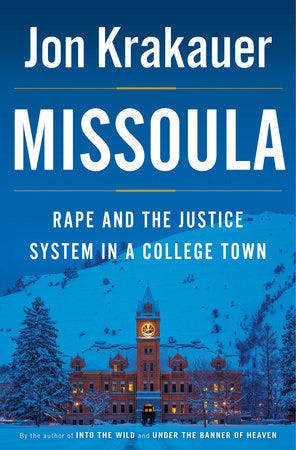

Recently, author Jon Krakauer filed a petition for a writ of certiorari, asking the U.S. Supreme Court to take up his public records lawsuit against Montana’s Office of the Commissioner of Higher Education, which denied him records relating to the expulsion and reinstatement of a star college athlete accused of sexual assault.

Krakauer had initially sought the records while reporting on his 2015 book, “Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town,” which focused, in part, on how the University of Montana responded to a 2012 rape allegation made by a female student against the school’s starting quarterback, Jordan Johnson. Johnson was eventually acquitted of criminal charges by a jury, but not before UM moved to expel him.

However, the state’s Commissioner of Higher Education, Clayton Christian, overturned the university’s expulsion and Johnson remained enrolled at the Missoula campus. In the course of researching his book, Krakauer wanted to know the basis of Christian's decision and sought official records that might illuminate it.

“We suspected there was hanky-panky,” says Mike Meloy, Krakauer’s Montana-based attorney. “Obviously, something was going on.”

The university denied the request, contending that the records’ release would violate the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA. In turn, Krakauer sued.

Of all the mountains the alpinist author has climbed, this might be among the most daunting — and consequential.

“If ever there was a federal statute crying out to be clarified, it is FERPA,” says Frank LoMonte, director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida.

Anybody who has made even a few records requests of public universities has likely been treated to the mental lobotomy that comes from school lawyers claiming FERPA exemptions. If you really enjoy being gaslighted, do as we’ve done over the last few months.

In theory, this power-of-the-purse statute, enacted in 1974, prohibits the federal funding of state education institutions that have a policy or practice of releasing students’ “educational records” without their parents’ consent.

However, in the 45 years since its adoption, FERPA has increasingly become higher ed’s reflexive response to even the slightest inkling of public inquiry — a scrutiny sneeze, so to speak.

Make enough records requests of public universities and you’ll see that practically anything can (and inevitably will) be considered an “educational record” exempt from disclosure “pursuant to” FERPA.

Hell, here’s a FERPA-related records denial Daniel just received, courtesy of the University of Georgia, while typing the preceding paragraph:

The documents you have requested…consist of student education records and are therefore exempt from production under the Georgia Open Records Act pursuant to O.C.G.A. § 50-18-72(a)(1) and (37), which specifically incorporates the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99).

Unfortunately, since passing the law, Congress has done little to rein in its dizzying misapplication as a public records brush-off. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court hasn’t touched FERPA since its 2002 ruling in Gonzaga University v. Doe, which found that individuals cannot sue to enforce the statute’s privacy provisions.

LoMonte says he can’t recall a “serious effort” at trying to get a FERPA case in front of SCOTUS since.

“What makes FERPA so difficult is that the [privacy] right is always a state-protected right and not a federally protected right, “LoMonte says. “The question is whether FERPA preempts or supersedes the state law — and that makes it a really tricky bank shot to get into the Court.”

Krakauer’s lawsuit has already endured five years of whiplash on a roller-coaster ride through Montana’s judiciary: a state district court judge initially ruled in the author’s favor; on appeal, the state Supreme Court remanded the case back to the district court; the original judge was disqualified; a new judge ordered the documents be submitted in chambers; he again ruled the records should be released to Krakauer; the case went back to the state Supreme Court, which ultimately reversed the lower court’s ruling this past July.

Afterwards, Krakauer publicly vowed to fight on, telling the Associated Press he had a “moral obligation” to do so. In his cert petition, filed on Oct. 31, lawyer Meloy boiled the matter down to a fundamental question:

Does FERPA confer an individual right to privacy sufficient to block a court from ordering the release of personally identifiable information about a high profile university athlete on an issue of compelling public interest?

LoMonte, who contributed to a Montana Supreme Court amici brief in support of Krakauer’s case, says that while SCOTUS is typically loathe to weigh in on state-protected rights, it may find this particular case worth taking up.

“One reason that this is a promising case is that Montana doesn’t just have a (public records) statute but a constitutional right of access to public records,” LoMonte says. “So, this federal statute is being read to deprive people of a state-protected constitutional right, which is a very extreme way to read a federal statute.”

Daniel Libit and Luke Cyphers, coeditors of The Intercollegiate, write Newsletter of Intent each week. You can reach them with questions, comments, tips and FERPA-related denials at dlibit@theintercollegiate.com and lcyphers@theintercollegiate.com.

Featured photo illustration by Newsletter of Intent / jesseorrico.com / Wikimedia Commons; Zion Williamson photo courtesy of Keenan Hairston (Wikimedia Commons)

The Intercollegiate is proud to partner with the College Sport Research Institute, an academic center housed within the Department of Sport and Entertainment Management at the University of South Carolina. CSRI’s mission is to encourage and support interdisciplinary and inter-university collaborative college-sport research, serve as a research consortium for college-sport researchers from across the United States, and disseminate college-sport research results to academics, college-sport practitioners and the general public. You can learn more by visiting CSRI’s website.