This is Newsletter of Intent, an occasional emailed dispatch about college sports issues from The Intercollegiate.

Ready to commit to your college sports education?

By Luke Cyphers and Daniel Libit

(A note to subscribers: Due to the length of today’s Newsletter of Intent, it may be truncated in your inbox. If so, you can be certain to read it in its entirety on our Substack page here.)

An in-depth investigative series by USA Today on dozens of college athletes who transferred between NCAA institutions, despite previously being disciplined for sexual offenses, could be expected to generate commotion.

“The Predator Pipeline” certainly did that. The surprise was that some of the most heated debates came from an unexpected corner of the Twitterverse: an intramural fight among advocates for college sports reform.

Advocates for athlete rights, such as attorney Richard Johnson and former Duke lacrosse player Maddie Salamone, took issue with the framing of the series and some of its conclusions, while sexual-abuse victims advocates, such as Katherine Redmond and Brenda Tracy, took issue with the issue-takers.

The social-media dustup laid bare a reality that’s little discussed in the coverage of the recent wave of efforts to call the NCAA to account: While college athletics is the target of what can accurately be described as a vital, maybe even historic, reform movement, not all reformers want the same things.

From those who worry about athletes coming away with too little from the multi-billion-dollar industry they labor in; to those who worry about athletes getting away with too much; to those who care about gender equity among athletes; to those fighting to subordinate athletics to the educational mission of universities; to, well, name your beef with college sports, and someone’s out there beefing about it, too—all of these factions are trying to inhabit what is, if not yet a big tent, a diverse and potentially unruly one.

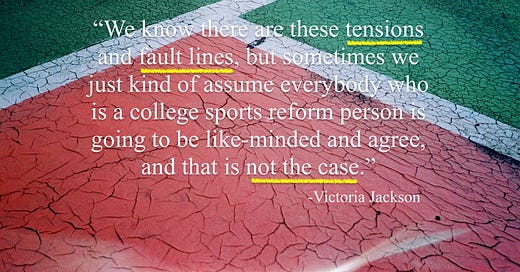

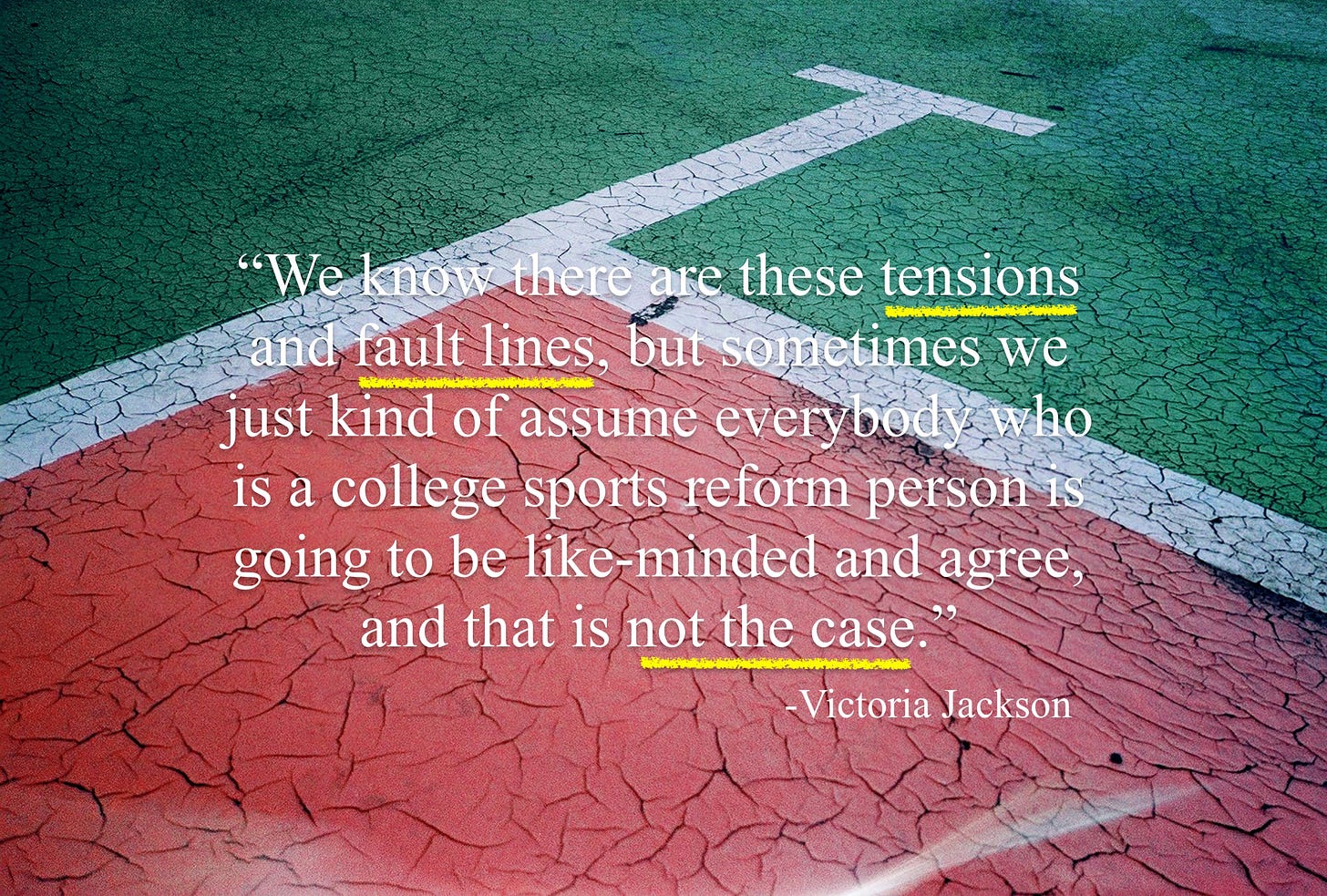

“I don’t think we think that much about it,” says Victoria Jackson, a former college track athlete who teaches sports history at Arizona State. "We know there are these tensions and fault lines, but sometimes we just kind of assume everybody who is a college sports reform person is going to be like-minded and agree, and that is not the case.”

Tensions among these factions are surfacing, probably not coincidentally, amid a time of great hope that the NCAA is finally on its heels. Court cases have nibbled away at the underpinnings of the NCAA’s draconian restrictions on athletes’ rights over the past decade. California’s passage of a law allowing college athletes to capitalize on their names, images and likenesses (NIL) set off a wave of copycat bills in other states. Federal legislation looking to overhaul college sports governance has been introduced. A rival basketball league, which will pay college players a salary and allow them to make as much money as they want from endorsements, plans to begin play in 2021.

All the while, mounting revelations of academic fraud, sexual assault cover-ups, under-the-table sneaker-company payoffs, exploding salaries for coaches and administrators, and bizarre readings of the bloated amateurism rulebook have left the NCAA with precious little moral high ground for “the collegiate model” to stand on.

Not that it’ll stop trying.

At last week’s national NCAA Convention in Anaheim, Calif., the power-wielders of college sports gave various winks and nods at and vowed to deliberate over some of these points of contention. Scarcely anyone we spoke to is holding their breath.

Nearly everyone in this story — from the more conservative college sports reformers to the most nihilistic — agree on this much: the NCAA sucks, and irredeemably so. Most also agree that the current system of college sports selectively serves to enrich a small, elite group of rich, primarily white, men. Beyond that, in diagnosing the underlying disorder or prescribing its most effective remedy, it gets complicated.

Each new crack in the governing body’s armor creates different ideas on how to exploit it for the betterment of athletes, the broader university communities, the taxpayers who underwrite much of the college sports infrastructure, and even the sports themselves.

Those divergent perspectives can create rifts, exemplified by the fight over the USA Today investigation into college athlete perpetrators. But there are other disputes, as well, namely over the issue of player compensation. While name-image-likeness legislation has served as a major catalyst for the current reform movement, the California law and its successor bills make for “an idiosyncratic tipping point,” says Donna Lopiano, a former sports administrator at Texas and one-time head of the Women’s Sports Foundation, because NIL wasn’t atop the to-do list for most reformers and was often seen as a half-measure.

Real reform debates, and genuine reformer divides, more often center on whether and how much athletes in revenue-generating sports such as football and basketball should be paid — which makes sense, given the billions of dollars the NCAA rakes in from its TV contracts and tournaments.

“We have had lots of sniping, already,” says B. David Ridpath, an associate professor of sports management at Ohio University.

The clashes between reformers can resemble — if not serve as proxies for — the kind of friendly fire one finds rivening the political Left ahead of November. “Using the Democratic Party as an example here, they have one goal, and that’s to beat Donald Trump,” Ridpath says. “And at some point in time they’re going to come together to do that. If they undermine each other, they’re going to lose out on that goal.”

Further agitating the movement is the concern that this opportune moment — in which public attention and bipartisan political interest have neatly coalesced around college sport’s shortcomings — is fleeting. How reformers deal with this opportunity, especially on the federal level, could determine whether any real change comes to college sports any time soon, says Ramogi Huma, founder and executive director of the National College Players Association, a nonprofit that advocates for greater player economic rights and health protections.

"It feels like the fourth quarter,” says Huma, “when everything is hanging in the balance.”

Who are the groups and individuals pushing the current reform movement? What are their various goals, priorities, tactics? And where do those goals and priorities collide with each other?

To get our arms around it, we spoke with more than a dozen prominent or influential voices in the arena — or multiple arenas, including athlete compensation, academic integrity, gender equity, and athlete health.

We asked our sources how they identified their roles in the movement, where it stands today and what direction it’s headed, and especially, what kinds of internal conflicts could hinder progress in changing college sports.

We immediately identified one line of schism: Advocates who believe college sports’ exploitative economic model is the most pressing issue, and those who come at NCAA reform believing education, gender equity, or health and safety issues are paramount.

Of course, these concerns exist on a continuum and frequently overlap, with many a reformer in more than one camp for reasons that sometimes have as much to do with philosophical differences as they do with their professions (lawyers vs. economists vs. academics), personal connections to college sports (athletes vs. non-athletes), gender and race. Even among the likest of minds, there are myriad debates over the way to manifest change.

For example, the economic reformers harbor multiple (and at times conflicting) theories on how best to skin the fat NCAA cat, whether it be through the courts, legislatures, trade unions, or new kinds of organizing.

College sports reform efforts are as old as college sports, with the NCAA itself being founded as a means to quell the alarming death toll in football in the early 20th century. But it’s important to take stock in how rapidly the reform movement has evolved of late.

In 2009, Allen Sack, a sociologist and sports management professor at the University of New Haven, penned a study for the Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, which sought to “identify the issues and assumptions that divide reformers and reform groups.”

Sack divided college sports reformers into three categories:

“Academic capitalists” who emphasize “the importance of the bottom line,” assume “big-time college athletes are amateurs engaging in sports as a vocation,” and “view extracurricular activities as equal in importance to what is taught in the classroom or laboratory.”

“Athletes rights” advocates who “assume that collegiate sport as commercial entertainment is deeply embedded in the fabric of American life” and “view athletic scholarships as contracts for hire, not educational gifts.”

“Intellectual elites” who “argue that highly commercialized athletics has a negative effect on American higher education” and “are unrelenting in their criticism of athletic commercialism.”

The contours of those categories have changed over the last decade but, for at least that long, the hub of the intellectual elite crowd has been a think tank Sack remains deeply involved in, The Drake Group, whose own history provides a salient example of how disorderly college sports reform can be.

The Drake Group was founded in 1999 by Jon Ericson, a former provost at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, who had previously written a book, “While Faculty Sleep: Intercollegiate Athletics and Feel-good Reform.”

At Ericson’s behest, the original charge of The Drake Group was to address the corrupting influence of college sports on the academy, and TDG’s membership almost exclusively consisted of faculty from universities around the country.

In fact, the group’s original proposed name was the National Association of Faculty for College Athletic Reform — or NAFCAR — but The Drake Group ultimately stuck, even though only Ericson was affiliated with the eponymous university.

The Drake Group’s “intellectual elitist” reform agenda, as Sack noted in his study, included proposals of replacing one-year-renewable athletic scholarships with those independent of athletic performance, ensuring athletes could pursue the major of their choice, and “closely monitoring the growth rate of operating expenditures in sports.”

In addition, The Drake Group served as a kind of morale booster for college faculty in the face of what they perceived as college sport’s encroachment upon its core educational mission.

“It was a whistleblower support group, to some extent,” says Jason Lanter, who served as The Drake Group’s president from 2010 to 2012.

But it was not exactly athlete-centric. Kenneth Shropshire, a former Stanford football player who is now CEO of Arizona State’s Global Sport Institute, recalls recoiling in attendance at TDG’s debut gathering when he was a professor at Penn.

“There’s a photo in the bowels of the Internet of me explaining the Buckley Amendment to The Drake Group,” says Shropshire, who coauthored the 2017 book, “The Miseducation of the Student Athlete: How to Fix College Sports.”

“At this first meeting,” Shropshire says, “my first and only meeting, there was a discussion that we should disclose the grades of all these students and all of the courses they’re taking, so we can put sunshine on this whole thing. I was outraged. It was really not understanding the rights of these athletes.”

Since those early days, Shropshire adds, The Drake Group’s thinking evolved. “It is a key player in the struggle,” he says, and over the years, the group’s reputation grew. It counted as members some of the country’s most prominent scholars in the critical study of college sports, including Drexel University sports management professor Ellen Staurowsky, Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist and Richard Southall, director of the College Sport Research Institute. (Disclosure: CSRI and The Intercollegiate have a formal partnership, however CSRI had no editorial involvement in this article.)

But TDG’s core membership has never grown much past a dozen.

“One of the challenges is most faculty don’t get involved until they have to get involved,” says Lanter, who served as president from 2010 to 2012. “It is only when athletics come into play in their daily lives that they may reach out. It is hard to get starting assistant professors to join The Drake Group.”

While TDG would occasionally engage with the NCAA over its reform proposals, it regarded itself as a much more independent and unfettered organization than, say, the Knight Foundation Commission, which had formal tie-ins with the NCAA. By contrast, The Drake Group could exhibit a contrarian streak, hosting, for a number of years, a counter-programming convention at the sites of the NCAA men’s basketball Final Four.

Ridpath, an early TDG member who currently serves as its interim president, recalls the group’s creative, and successful, efforts to garner media attention, such forming a picket line in front of the coaches’ hotel at the Final Four and naming one of its awards for Robert Maynard Hutchins, the University of Chicago president who dropped football in 1939 and pulled his school out of the Big Ten Conference. “We got a lot of press coverage,” Ridpath says.

But a decade into its existence, The Drake Group had little real-world progress to show for its efforts. If anything, things had only gotten worse on the academic integrity front, as evidenced by the University of North Carolina “paper class” scandal in 2011.

The Drake Group’s major turning point came in 2013, when Sack, then its president, brought Donna Lopiano into the fold.

“I was constantly and throughout most of my life a dyed-in-the-wool athlete rights guys,” says Sack. “I have moderated to a certain degree.”

Credit — or blame — Lopiano for his shift.

Sack tells of a come-to-Jesus moment over dinner with Lopiano at a Chinese restaurant in New Haven, Conn., when she proposed to him a Congressional solution for college sports reform — one she argued would require TDG to change its disposition from irascible sideline critic to productive change agent.

The big concession would be to give the NCAA a “limited antitrust exemption,” as Sack describes it, something it had long coveted. Lopiano’s case was that you needed a big enough chip to offer if The Drake Group ever truly hoped to rein in the commercialism of college sports, as was its organizing principle.

“It kind of gave up a little bit on the faculty,” Lopiano acknowledges. “We didn’t see how we had any power — the NCAA is this big, behemoth thing, and everybody agreed that faculty wasn’t going to stand up. The theory of Congressional change is you don’t need the masses, you don’t need a lot of power, you do need access to tipping-point people in Congress.”

With Lopiano and Zimbalist taking the lead, TDG proposed federal legislation called the College Athlete Protection (CAP) Act, which included a series of provisions aimed at increasing financial support and medical benefits for college athletes while restoring “the ability of national governance associations to combat commercial excesses.”

The CAP Act provided for college athletes the right to benefit from their name, image and likeness, an idea that had been championed for years by Zimbalist, and which has now taken hold everywhere.

But the CAP Act’s proposed antitrust exemption, however limited, struck a core Drake constituency as an unholy capitulation to the NCAA at precisely a time when the Ed O’Bannon v. NCAA antitrust case was seen as a game-changer. While Lopiano aggressively lobbied Congress to bring about the CAP Act, roughly half of Drake’s executive board — including Staurowksy and Lanter — cut ties with the group.

Sack describes the fallout as “one of the most painful things in my life.”

“I was a pariah for a while,” says Sack. “They wouldn’t listen to me. They thought I was supporting a total antitrust exemption, which would allow the NCAA to get away from O’Bannon.”

Staurowsky says she has still not received a satisfactory explanation for what transpired.

“The Drake Group’s abrupt reversal from being supportive of O’Bannon — and, within weeks of submitting amicus brief in support of O’Bannon — to [then] echoing the NCAA talking points, seemed very puzzling to me,” Staurowky tells Newsletter of Intent.

Lanter says his bigger concern with TDG was how it began juggling too many balls — like head injuries and NIL — that he felt had nothing to do with the cause of academic integrity.

“Where is the line with the original stated mission and vision?” Lanter says.

These days, The Drake Group, whose motto remains, “We Are The People Defending Academic Integrity,” highlights 19 different “issues” of concern on its website, from gender equity to athlete rights. And there continues to be upheaval among its ranks.

Two months ago, Fritz Polite, an assistant vice president and chair of the sports management department at Shenandoah University in Virginia, prematurely stepped down as TDG’s president because of his concerns with the organization’s direction.

“I thought they were veering off into other areas,” Polite says. “I think we should stay focussed on the academic integrity piece.”

Lopiano is now The Drake Group’s president-in-waiting, due to officially take the reins from Ridpath on July 1.

When it comes to athlete compensation, Lopiano and Sack, who is now retired from the University of New Haven but continues to serve on TDG’s board, want reform to stop at the water’s edge of NIL. Opening a completely free market to athletes, they argue, will only further disconnect college sports from higher education.

“Athletes’ rights have risen to the top and there has been an increased acceptance of commercialized sport to the point where even academicians are throwing their hands up and saying, ‘Pay the athletes,’” says Lopiano.

The Drake Group has been the main engine behind a bipartisan House bill proposed last month by Florida Reps. Donna Shalala — a former college president at the Universities of Wisconsin and Miami — and Ross Spano, which would create a Congressional blue-ribbon panel to explore a broad list of college sports reform concerns, many of which mimic the provisions of the CAP Act Lopiano pushed for seven years ago.

Huma doesn’t support the Shalala bill, because he doesn’t trust the NCAA with any kind of antitrust exemption, big or small. He thinks legislative efforts to cut coaching salaries and athletic department costs will have a perverse effect: ensconcing college athletes as unpaid laborers under federal law.

“I don’t see that as advocacy for players,” Huma says of The Drake Group’s lobbying. “It’s actually adopted a lot of the goals that we’ve been fighting for for a long time, but I think also, partly, it’s being used as a Trojan Horse to attack players’ rights when it comes to economics.”

Staurowksy, meanwhile, has joined a recently created NCPA oversight board, most of whose members, including Salamone and Victoria Jackson, describe themselves as “athlete advocates.”

In the current college sports reform schema, Richard Johnson considers The Drake Group and the NCPA as merely “marginal critics” of the NCAA. But few voices in this space are as demonstrative and, at times, antagonistic, as Johnson’s.

A plaintiff’s legal malpractice lawyer based in Cleveland, Johnson represented baseball players Andy Oliver and James Paxton in their separate NCAA eligibility cases, ultimately winning Oliver a $750,000 settlement. He subsequently published a 638-page article about the case’s significance in the Florida Coastal Law Review.

Johnson counts himself among the NCAA’s “outspoken critics” — who, in his telling, are the ones that count. Johnson includes in this category academics like Staurowksy, Southall, Houston’s Billy Hawkins, and Eastern Michigan’s Richard Karcher; historian Taylor Branch; journalist and author Joe Nocera; and former shoe company executive and pay-the-player advocate Sonny Vaccaro.

“Maybe ‘intellectually honest’ is a better way to describe outspoken,” says Karcher, a former law professor who has been publicly critical about the way the California NIL law was written. (Karcher served as an expert witness for Johnson in both cases.)

Staurowsky, for her part, chafes at the term “critic,” saying it plays into a rhetorical trap set by college sports institutionalists, like former NCAA President Myles Brand, who have sought to diminish scholarship critical of the business practices of college sports.

Staurowsky divides the reform landscape into those whose focus is “player-centered” and “institutional-centered.”

"Efforts to ‘reform’ college sport by adjusting existing sport governing bodies (NCAA, conferences) are misplaced,” she says. “The structural issue is to create a counterbalance to the power wielded by the NCAA and conferences by empowering athletes with individuals who represent their interest.”

That’s what Andy Schwarz believes he is doing by co-founding the Professional Collegiate League, set to begin play in the summer of 2021 with a model that pays its players a salary and allows them to earn as much endorsement money as the market will bear. An economist who worked as an adviser in the O’Bannon case, Schwarz sees the new league as a way to offer college players full economic rights that the NCAA has resisted through its fusty amateurism model.

The PCL’s view is that NCAA “reform” isn’t the answer, Schwarz says, “as it will inevitably result in compromising in key areas. As a league, we're entirely focused on creating a professional, equitable option, rather than concerning ourselves with where we stand in comparison to the NCAA. We think we’ll get there first, and whether the NCAA ever gets there becomes somewhat moot.”

Schwarz may not believe in NCAA reform, but he doesn’t loathe college sports, either. “I think colleges should be in whatever economic market space they want to be,” he says. “Money is not inherently evil… I think college can and should be in this space if they can do it legally and ethically.”

Hawkins, who wrote the 2010 book, “The New Plantation: Black Athletes, College Sports, and Predominantly White NCAA Institutions,” likewise doesn’t seek the end of college sports as we know it.

“I see the good in it,” he says. “I have been in close proximity to see there is a lot of good being done. But it is an unstoppable commercial machine that we are trying to grab hold of, and a lot of the time a lot of individuals are getting ground up in this whole process.”

The problem is irreconcilable, according to Southall of the CSRI, whose advisory board features Sack, Staurowsky, Johnson and Polite. In Southall’s view, there’s really no ethically sustainable way to be a college sports reformer, at this point.

"You cannot reform something that is immoral,” he says. "I think some reformers wish that college sport was the mythology that the NCAA had created. And so for them, reform is controlling coaches salaries, (and) having stricter admissions standards so that the athletes are real students and not taking fake classes. In many ways, I don’t think some folks like the college athletes in football and basketball in the Power 5. I think there are some elements of class that are also elements of race or ethnicity in play here."

For Johnson, race must be at the very center of the college sports reform conversation. Indeed, one of Johnson’s biggest criticisms of the recent antitrust litigation targeting the NCAA in the O’Bannon and Alston antitrust cases is that they didn’t sufficiently make a race case, highlighting the disproportionate numbers of black athletes who participate in college sports’ revenue-generating sports.

Johnson, who is white, says his sensitivity to racial discrimination has intensified in his latter years because of his marriage to his husband, a black physician from Jamaica.

“I have watched how he has had to struggle,” Johnson says. “I have become, over the last 10 years, incredibly sensitized to economic power, civil rights as they effect gay people, and civil rights as they effect black people — and by extension other minorities.”

That is the prism through which Johnson says he read USA Today’s “Predator Pipeline” series and combatively took to Twitter to confront what he perceived to be its dangerous racial implications. (The series’ author, journalist Kenny Jacoby, discussed his reporting with Daniel in Episode 7 of The Intercollegiate Podcast.)

This put Johnson at odds with Brenda Tracy and Katherine Redmond, two advocates for survivors of sexual assault committed by college athletes. Tracy, who, in 1998, reported to police being gang-raped by four men, including two Oregon State football players, now leads an initiative called #SettheExpectation and has lobbied athletic departments, conferences and the NCAA to adopt a zero-tolerance policy for sexual assault, which she has codified as the Tracy Rule.

Redmond was a student at the University of Nebraska who successfully sued the school for violating Title IX after she went public about being assaulted by a Cornhusker football player in the 1990s. She went on to found the National Coalition Against Violent Athletes.

Joining the online scrum was Salamone, a former chair of the NCAA’s Student Athlete Advisory Committee, who mostly sided with Johnson. (Disclosure: Salamone is a contributor to The Intercollegiate Podcast).

The resulting confrontation, which ramified across several Twitter threads, was ostensibly about the practicality and legality of an NCAA rule forbidding sexual assault perpetrators from playing college sports. But if you went down the rabbit hole — and we’ll let you do so on your own accord — it became a deeper, more fraught clash about issues like race and gender.

As Shropshire notes, when the NCAA was forced by reformers to open up transfer rules, it allowed more freedom of movement for athletes, which includes more freedom of movement for athletes with bad acts in their past. So something seen as institutional progress may have created an unintended consequence.

It’s a problem indicative of the NCAA’s business model, one too often based on greed, says Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a former Duke swimmer and Olympic gold medalist who now runs Champion Women, which promotes opportunity for girls and women in sports. “One of the ways they’re greedy is they’re not willing to absorb the cost of bringing a sexual predator onto campus,” she says. “The cost will be borne by the women on the campus. That’s an externality that needs to be changed.”

Salamone and Johnson believe the Tracy Rule unnecessarily and unfairly targets college athletes, who themselves represent the ultimate victim class in college sports. Tracy and Redmond believe there is sufficient data to justify focusing specifically on college athletes who perpetrate sexual assault. Johnson and Salamone don’t.

Johnson also worries certain kinds of advocacy divert public attention from athlete-rights reforms.

“We have one gallon of energy,” says Johnson. “We only have so much to use and we have to maximize its effectiveness. If you want to talk about sexual misconduct, we’ll talk about sexual misconduct on campus. We are not going to take it down to a microscopic level to have it target football players.”

Victoria Jackson, who ran track at North Carolina (and wrote her doctoral dissertation on 50 years of Tar Heel female sport history) makes a similar limited-resources argument as Johnson, but with a different target: She has argued that gender equity is less important than giving the revenue-generating athletes the opportunity to fully enjoy the fruits of their labor.

In a much talked-of Los Angeles Times op-ed she authored two years ago, Jackson decried modern college sports as the “21st century Jim Crow.” A white woman, Jackson asserts that there’s a zero-sum game between the Title IX activists and race-conscious athlete rights reformers.

“I simply can't morally advocate for more resources going to women's sports, even when schools might be out of compliance with Title IX — at least at Power 5 institutions, where I focus my work — because we have not been good allies,” says Jackson. “Title IX is great. But we can't be advocates for women's sports in a vacuum.”

Not surprisingly, Hogshead-Makar, who has spent much of her 30-year legal career pushing schools to comply with federal law under Title IX, says any reform that sacrifices women isn’t worthy of the term.

“I don’t think you can have reform that only seeks to protect one group of people,” says Hogshead-Makar. “It’s not just going to protect the athletes that are competing. The reform also has to have an impact on women being able to participate, and on sexual violence. I just can’t imagine any reform that wouldn’t have an impact on making sports more gender equitable on campuses.”

Redmond doesn’t buy Johnson’s notion of a scarcity dilemma, either. “Why wouldn’t you take on the NCAA from multiple angles?” she asks. “Why would you just focus on one area, instead of getting at all of the NCAA issues, sports issues, so that the NCAA has to take this on on a number of fronts?”

In fact, Redmond sees player compensation and sexual assault awareness as mutually reinforcing advocacies. Redmond grew up a college sports fan; her father played baseball at Nebraska. But she’s seen enough corruption of the NCAA and the system surrounding it — from boosters to local law enforcement — to believe it’s irreparable, and says the best way to heal college sports is to privatize it and remove the taxpayer subsidies NCAA teams currently enjoy thanks to their attachment to the education system. “I’m all for paying the athletes,” she says. “Because when victims go to sue (currently), they will usually sue the university, and not the athlete himself.”

Paying players “allows a path to that,” Redmond says. “And it allows a path to privatization. That’s why I’m for it.”

Adds Tracy, “As an advocate and survivor, I’m not competing with others who are championing important sports reform issues. I believe there is room for everyone.”

In the case of Cody McDavis, though, that room may not be comfortable.

Perhaps nobody exemplifies the weird intersectionality that arises from the reform efforts than McDavis. A former Division I basketball player at the University of Northern Colorado, McDavis became active in efforts to speak out against and prevent sexual abuse among athletes, working closely with Tracy’s #SettheExpectation campaign. But he became a national lightning rod early last year, when he wrote a New York Times op-ed, which criticized proposals to pay college players, and subsequently took to cable TV to defend the NCAA’s position on amateurism.

“Those are two definitely divergent opinions,” says McDavis, who since graduating from college earned a law degree from UCLA and now works for a firm in San Francisco. “I’m of the opinion that the NCAA is in the right with their stance on amateurism, and in the wrong in their lack of having a stance at all on sexual-violence prevention and policies.”

Although the NCAA has no doubt found McDavis’s friendly voice useful — having featured him in several promotional video clips over the years — McDavis rejects the idea that he is a tool for the status quo.

“I don’t have a blind support for the association,” he says. “I think it does good things and I’m willing to look at it objectively. But when I came out with my stance on pay-for-play, and people read it, they made sure I knew they were against it. I know what it’s like to put an opinion that ruffles feathers. People will come out in droves to make sure that I’m aware that they think my opinion is asinine. I have not had a single response like that to my advocacy in calling for the NCAA to reform its sexual violence policy. Not a single one. It’s been universal support or just crickets.”

McDavis says his background informs both positions. Raised by a single mother, he says he saw family members cope with sexual violence. And growing up poor, he says the basketball scholarship changed his life. “I had about $1,000 a month given to me in a stipend, and I pocketed about $300 of that after taking care of rent (and) food,” he says. “The rest, I didn’t need it—so it went into a savings account, every month that I was in college.”

According to McDavis, he graduated with $10,000 in the bank.

“I came to see what you can get out of college if you appreciate it,” he says.

Some of McDavis’ critics have accused him of selling out to the NCAA, or of having something akin to Marx’s “false consciousness” about player exploitation. McDavis argues the real falsity is allowing commercialism to trump education, and believing that even more commercialism, this time from the players’ side, will make things better.

“The truth is when you pay student athletes, you are doubling down on the idea that you are there to win, to play sports,” says McDavis. “You can’t pay someone to be a great athlete and expect them to be excellent at anything else if all their incentives are in athletics.”

In an interview with NOI, McDavis gave a sanguine accounting of his past collisions with athlete-rights reformers. “I don’t disrespect or take anything away from other opinions,” he says. “I just disagree, and that’s OK. That’s where change happens. If everybody’s in agreement, you’re doing something wrong.”

That sanguineness, however, may bely the tumult that McDavis has been part of in recent years, while jousting online, sometimes quite bitterly, with pay-the-player proponents. His social-media sparring partners have included Ridpath, Salamone, ESPN announcer Jay Bilas, law professor Marc Edelman and Schwarz, who was compelled to turn one of their Twitter tiffs into a multi-part blog series. McDavis has more recently made his Twitter private, citing personal reasons.

Meanwhile, misgivings about McDavis have sometimes redounded to Tracy.

“I think it totally discredits her,” says Salamone. “On the one hand, you are crafting a rule that specifically targets athletes, ignoring the fact there are sexual assaulters and perpetrators who are not athletes. And you are aligning with someone who is adopting some of the NCAA nonsense and excuses [on amateurism].”

Tracy says she has not sufficiently researched the athlete compensation issue to “form a responsible opinion” and has no intention to stake one out publicly.

Salamone adds: “What annoyed me about this [Twitter] conversation is people on the same side of the cause — Brenda and I want the same thing: we want fewer to be hurt; we want fewer victims; the system to run fairly; and for athletes to be given a good chance and protected; and for people to be protected — when advocates are fighting each other, it is so pointless.”

Can competing ideas among reformers be sufficiently resolved to make the moment count? That remains an open question.

Shropshire and Hogshead-Makar both point to an original sin baked into American athletics that makes it so resistant to reform: the fractured nature of the system.

“Every other country has a minister of sport,” says Hogshead-Makar. “And we don’t.”

The U.S., she says, could be like other nations who have “a holistic look: What’s the best way to nurture talent, what’s the best way to make a healthy population (allowing) everybody to participate, what’s the best bang for the buck?”

Instead, with no single entity governing national sports, and with two of the most popular sports — football and basketball — enmeshed in the higher-education system, the governance resembles a collection of feudal fiefs often at war with one another. NCAA policies look awful, as do national Olympic committee policies, and state high-school policies, and local travel-team policies — if those even exist.

That’s why you can expect more discord, and shifting alliances, in the coming years as reformers attempt to change college sports. Consider the Shalala bill. The legislation authorizes an independent federal commission to study college athletics, which seems agreeable enough, but which some reformers fret might be the first step in a slow, bureaucratic death march to nowhere.

There are the debates over what such a commission should study: Both the NCPA and The Drake Group support NIL protections for athletes, but those like Zimbalist believe NIL must be regulated to prevent abuses, e.g., a booster paying a recruit $50,000 for NIL in return for a luxury stadium suite from the college sports program. Huma and the NCPA, on the other hand, want no legal caps on athlete earnings, and fear the college adminstrators marshalling their nationwide lobbying power to game the federal debate, so that NCAA rules, including limits on athlete compensation, are turned into the law of the land.

Like Huma, Redmond doesn’t agree with preserving NCAA amateurism, but she helped write TDG’s sexual-abuse policy.

“It lays the framework for basically forcing the NCAA or athletic departments to work in that area,” she says. “That’s not currently happening. Is it a cure-all? No, because it doesn’t get at the system, but it cracks the door open to legislation that will.”

Ridpath says the NCAA “could be brought down tomorrow” if players in the Power 5 conferences went on a general strike, and he believes societal changes make that a real possibility, “Athletes now as opposed to when I was growing up, they all know each other,” Ridpath says. “They can stay in touch for free on social media. When I was growing up you didn’t talk to rival athletes. Now these athletes talk to each other and they’re starting to realize collectively the voice they have. I give Ramogi a ton of credit.”

Ridpath points to the Missouri football team in 2015, which forced the resignation of the school’s president, then under fire for incidents of on-campus racism, by declaring they would not take the field in a regular-season game.

Karcher concurs.

“I've come to the point where I realize that any meaningful reform has to come from players taking the initiative to do something about it, as Billy Hawkins has talked about long before me, which certainly wouldn't happen without a major fight,” he says. “But Curt Flood did it. Because the football players in the Power 5 conferences possess incredible economic power, they actually have the ability to change the system.”

Huma knows this as well as anyone, but he also knows how difficult this simple-sounding solution is. Players who step out of line with their schools and speak up risk losing everything — scholarships, stipends, and in the cases of elite athletes, a chance to advance to the pros.

“That’s a hard dynamic,” Huma says. “I could dream up personally a million ways for college athletes to get involved and be active. But the reality is players typically don’t feel comfortable doing that. And that’s why in all these years you can look back and see how rare it is.”

Power resists change, as everyone working to reform college sports is well aware, and there’s rarely consensus on the best way to reform a cultural powerhouse like college sports. But despite the disagreements, change is happening nonetheless.

“There’s always a potential for divisiveness to hurt any reform movement,” says Zimbalist, “but I think at this point, the idea of NIL reform has penetrated into both political parties, and it’s penetrated from the radical left into the center of the political spectrum.”

And NIL may be the start of bigger reform, however one defines the term. As with so much else, we’ll know so much more come November. -30-

The New York Times has ended its weekly college basketball column with CBS Sports’ Jon Rothstein, NOI has learned, following our revelations last month of his hyper-friendly texting regimen with college basketball coaches.

On Dec. 17, we published screen grabs from a month’s worth of text messages between Rothstein and a randomly chosen sampling of eight D-I coaches, in which Rothstein wished them “good luck” before each of their games. The texts were obtained through FOIA requests we made to a couple dozen public universities.

“We experimented with a weekly report on college basketball but it did not find much of an audience and we discontinued it,” says Randal Archibold, the Times sports editor. Archibold says that the paper’s arrangement with Rothstein was always “informal” and that he was never placed under contract.

Rothstein began writing a weekly column for the Times on Nov. 8, but his byline hadn’t appeared in the newspaper (or on NYTimes.com) since his Dec. 16 piece, “College Basketball Is Wide Open, And Could Stay That Way,” which ran the day before NOI unveiled his SMS missives.

Although this curious journalism marriage has been annulled, Rothstein’s Twitter bio still anoints him as: “Contributor: NY Times.”

Since we last published, the University of New Mexico formally settled a public record’s lawsuit Daniel filed, by agreeing to pay $30,000 plus legal fees.

Daniel’s suit stemmed from UNM’s denial of several records requests he had made in late 2018, while still at the wheel of NMFishbowl.com. The university claimed Daniel’s requests lacked “reasonable particularity,” which was nonsense, as are far too many claimed exemptions by university records custodians.

But alas, some public good has come from it: We’re putting that full 30K to work in furtherance of The Intercollegiate’s journalism and awaiting our next opportunity to take a transparency-avoiding public institution to court. We’re open to suggestions. We’re also grateful for — and ultimately reliant on— financial contributions that aren’t the result of court-ordered mediation.

Luke Cyphers and Daniel Libit, coeditors of The Intercollegiate, write Newsletter of Intent. You can reach them with questions, comments, and tips at lcyphers@theintercollegiate.com and dlibit@theintercollegiate.com.

Featured photo by Bogdan Karlenko / Unsplash. Photo of The Drake Group’s 1999 meeting courtesy of The Drake Group. Photos of Donna Lopiano, Richard Johnson and Brenda Tracy provided by the subjects.